|

SILENT GENOCIDE

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES: THE RIGHT TO LIFE

International Day for the Elimination of

Racial Discrimination

March 21, 2011

|

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) -

Sharing Truth: Creating a National Research Centre on

Residential Schools, March 1-3, 2011, Vancouver, Canada

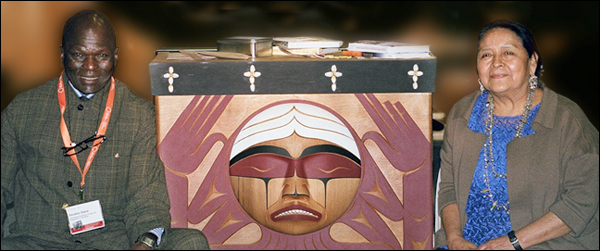

International Speakers, L-R, Doudou Diene, UN Special

Rapporteur for contemporary forms of racism, racial

discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance

(2002-2008) and Otilia Lux de Coti, member of Congress of

the Republic of Guatemala, vice-president of the United

Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2002-2007).

The TRC Bentwood Box, carved by Coast Salish artist Luke

Marston, is a lasting tribute to all Residential School

survivors and reflects the strength and resilience of

residential school survivors and their descendants, and

honours those survivors who are no longer living. |

A PERSONAL VISION ON SILENT GENOCIDE

NATALIE DRACHE

Editor/Publisher

Dialogue Between Nations |

For two

decades, I have been listening to Indigenous peoples from

all regions of the world attempting to bring attention to

what is happening to them in their communities and outside

of their communities: forced relocation; the scarring and

appropriation of their lands; the mutilation of the air, the

seas, rivers, earth, plants and animals, ourselves and all

our relations, disrespecting warnings, prophesies,

Indigenous true history, language and traditional knowledge.

The violent removal of children from their parents and the

abuses played out upon them; the annihilation of families

caught in the cross-fire of wars that are not of their own

making; and many other violations of individuals whose right

to exist is not respected.

I recently had the opportunity of attending Sharing Truth -

Creating a National Research Centre Forum on Residential

Schools, an initiative of the

Truth and Reconciliation

Commission of Canada. A number of international guest

speakers from several continents were invited to share their

knowledge with regards to the preservation of survivor

experiences. An evaluation of best practices is intended to

form the basis towards Establishing a National Memory, which

will contribute to the healing of the trauma experienced by

a large number of Aboriginal people and their communities,

as well as providing a living memorial to be shared with all

Canadians. Truth sharing circles were an integral component

of the forum, allowing survivors who chose to speak, an

opportunity to transform their sorrow and memories.

All this unexpectedly touched something that has been at the

core of my own emotional imbalance as I attempt to come to

grips with a recurrent theme, one which twists my soul,

leaves my throat dry, and heightens an internal shaking that

is the current of my most intimate fear. Immersed in the

generosity of the moment, I crossed over from being a

witness-by-profession and entered the circle of pain

alongside aboriginal survivors: forgotten children now being

remembered. When the feather and a stone was handed to me, I

offered up an apology for not knowing what had happened and

a second apology for not speaking out when I did know of the

existence of the residential schools. But more than that, it

was the first time that I no longer denied that lifelong

trauma which passes from one generation to the next, through

one century into another.

There are situations, past, present and ongoing of such

distress, which if widely considered, fall into the

definition of genocide. In some cases, determined acts of

genocide are localized, pre-meditated and legislated. In

other instances, genocide is the result of an acquired

attitude, very quiet and dispersed, so silent and almost

casually accepted, that the disappearances and deaths of

Indigenous individuals one by one, goes unnoticed. A family

disinherited, brutalized here, or there, living in fear and

trauma.

If one were to access reports on the number of Indigenous

people around the world suffering on a casualty by casualty

basis, there is no doubt in my mind we are talking about

millions of individuals caught up in a devastating holocaust

which continues to evolve, and to which there is a very

disturbing and almost passive lack of awareness.

Natalie Drache,

Canada

Editor/Publisher, Dialogue Between Nations

Delegate, Sharing Truth: Creating a National

Research Centre on Residential Schools |

Saying this, I have come to the conclusion that there is a

consistent and systemic movement of global proportions

consumed by an irresponsible inertia of ignorance turning

into subtle and invisible violence, which could potentially

lead to the elimination or total assimilation of Indigenous

peoples throughout the world. I call this horrific vision

Silent Genocide.

Because the scale of this movement is rarely visible beyond

immediate rights abuses, and the larger framework is almost

never given a context beyond local communities and national

borders, the scope of this tragedy is not readily apparent.

The accumulation of multiple violations worldwide is rarely

investigated, nor even considered by local media and justice

systems.

And in almost all seemingly invisible or non-violent cases,

the general public remains silent, either in ignorance,

complicity or denial, citizens whose moral response to the

idea that genocide attributed to them is insulting. Of

course, this might be an enormous and mistaken

generalization on my part as there are people of good faith,

compassion and trust who are working with and for Indigenous

people in a process of reconciliation and justice. This

attests to the fact that accountability rests with each

citizen in urging their country's government to comply and

act on the ground in accord with human rights and

humanitarian law. What is a country if it isn't you and I?

However, if my initial observation regarding the tragedy of

silent genocide, based upon factual evidence, including

testimony, memory and oral history is found to be wrong,

then I would hope that the current situation of Indigenous

Peoples and the potentiality of a uniquely different

relationship based upon the recognition and implementation of

their inherent rights, would eventually, over several

generations, lead to respect for Indigenous

self-determination comfortably co-existing on equal terms

with other societies.

|

Chief Wilton

Littlechild, Commissioner

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Independent expert, member of the United Nations

Permanent Forum

on Indigenous Issues, 2002 - 2007 |

The possibility of a peaceful relationship of Indigenous

nations within nation states, and vice-versa: nation states

respecting the traditional territories of Indigenous

peoples, nations, tribes and clans, and the realization of

such a constructive and positive vision, would most

certainly contribute to the stability and survival of our

shared modern world.

It is suggested in a not entirely universal concept of

evolving human rights, and within the definition of a

so-called civilized society, the current trauma of millions

of Indigenous individuals can, on one hand, be healed

through the elimination of racism, racial discrimination,

xenophobia and related intolerance. I see it more like the

elimination of the causes of the above. And I am speaking

here about a profound individual social, cultural and

political will leading to personal and collective

transformation.

Between all of us, we have some commonalities: many of us

carry some joys but all of us carry some scars. No one is

completely immune to pain in its directness and in its many

mental and psychological manifestations. Yet, we also have

the capacity of denial when it suits us as we become

de-sensitized to the pain in others or inflicted upon others

in a clash of worldviews and xenophobia.

This amazing ability to open up or/and close down on our

humanity, as easily as breathing in or breathing out, acts

as a form of protection and survival. It is often motivated

by the dichotomy of perception, as well as the multiplicity

of misconceptions we create on so many levels that impact

one another in accepting a friend or eliminating an enemy.

Who shall live and who shall die in a world which we

seemingly try to control through personal or collective

judgments?

As a child born in Vancouver, Canada on March 21, 1942,

enjoying the seasonal magic of the first day of spring, to

later in life discovering that because of a massacre in

Sharpeville, South Africa in 1960, this precious day of mine

lost its innocence. Or perhaps it was I who lost my

innocence. The United Nations chose to commemorate that

tragedy in Sharpeville by naming the 21st of March, the

International Day for the Elimination of Racial

Discrimination and I found my birthright catapulting down a

path over which I had no control. I can only hope that some

splinter of sacred intuition envelopes and protects me/all

of us like a parachute softly floating against free fall,

towards a world illuminated within a brilliant flash of

insight.

There is a journalistic ethic to be respected here, but I

believe it has been betrayed by a broken heart.

So I have to ask myself, and you also, why is it so

difficult, so challenging to embrace each other's distinct

and diverse right to life? Is it not possible to turn around

the devastating wave of silent genocide as perpetrated on

many of the nearly 400 million Indigenous people living in

our world today?

To all of you, survivors, witnesses and friends: our

humanity is on the table for debate and dialogue. Our

humanity is up for grabs. And so is our compassion. And our

silence.

Natalie Drache

Editor/Publisher

Dialogue Between Nations

Truth and Reconciliation

Commission of Canada

L-R Commissioner Marie Wilson, Commissioner Justice

Murray Sinclair,

Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild

TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION OF CANADA

COMMISSION DE VERITE ET RECONCILIATION DU CANADA

|

The truth telling and reconciliation process as part

of an overall holistic and comprehensive response to

the Indian Residential School legacy is a sincere

indication and acknowledgement of the injustices and

harms experienced by Aboriginal people and the need

for continued healing. The Truth and Reconciliation

Commission will build upon the Statement of

Reconciliation dated January 7,1998 and the

principles developed by the Working Group on Truth

and Reconciliation and of the Exploratory Dialogues

(1998-1999).

Le processus de vérité et de réconciliation, qui

s'inscrit dans une réponse holistique et globale aux

séquelles des pensionnats indiens, est une

indication et une reconnaissance sincères de

l'injustice et des torts causés aux Autochtones, de

même que du besoin de poursuivre la guérison. La

Commission de vérité et de réconciliation

s'inspirera de la Déclaration de réconciliation du 7

janvier 1998 et sur les principes établis par le

Groupe de travail sur la vérité et la réconciliation

et pendant les Dialogues exploratoires de 1998-1999. |

|

|

About

DBN |

Silent Genocide |

Vision |

Relationships |

History

|

Español/Spanish

|